This blog post continues a series about research into questions.

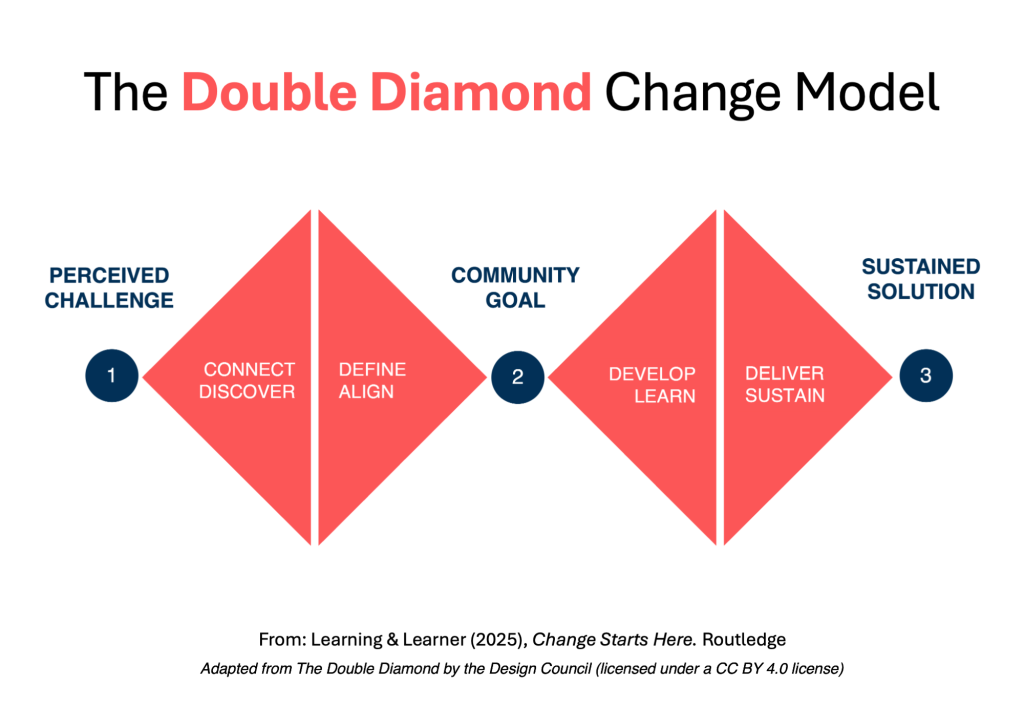

I started with questions that teachers should ask BEFORE students’ learning begins: “pre-questions,” measuring prior knowledge.

I then turned to questions that we ask DURING early learing: retrieval practice, checking for understanding.

Now — can you guess? — I’ll focus on questions that we ask LATER in learning, or “AFTER” learning.

To structure these posts, I’ve been focusing on three organizing questions:

When to ask this kind of question? (Before, during/early, during/later)

Who benefits most immediately from doing so?

What do we do with the answers?

Let’s dive in…

A Controversy Resolved?

At some point, almost all teaching units come to an end. When that happens, teachers want to know: “how much did my students learn?”

To find out, we typically ask students questions. We might call these questions “quizzes” or “tests” or “assessements” or “projects.”

Whatever we call such questions, students answer by writing or saying or doing something.

Who benefits from all these activities? Well, here we arrive at a controversy, because reasonable people disagree on this point.

OVER HERE, some folks argue that assessments basically benefits school systems — and harm others. After assessments, school systems can…

- sort students into groups by grade, or

- boast about their rising standardized test scores, or

- evaluate teachers based on such numbers.

I don’t doubt that, in some cases, assessments serve these purposes and no others.

OVER THERE, more optimistically, others argue that assessments can benefit both teacher and student.

Students benefit because

- They learn how much they did or didn’t learn: an essential step for metacognition; and

- The act of answering these questions in fact helps students solidify their learning (that’s “retrieval practice,” or “the testing effect”).

Teachers benefit because

- We learn how much our teaching strategies have helped students learn, and

- In cumulative classes, we know what kinds of foundational knowledge our students have for the next unit. (If my students do well on the “comedy/tragedy” project, I can plan a more ambitious “bildungsroman” unit for their upcoming work.)

In other words: final assessments and grades certainly be critiqued. At the same time, as long as they’re required, we should be aware of and focus on their potential benefits.

Digging Deeper

While I do think we have to understand the role of tests/exams/capstone projects at the “end” of learning, I do want to back up a step to think about an intermediate step.

To do so, I want to focus on generative questions — especially as described by Zoe and Mark Enser’s excellent book on the topic.*

As the Ensers describe, generative questions require students to select, organize, and integrate information — much of which is already stored in long-term memory.

So:

Retrieval practice: define “bildungsroman.”

Generative learning: can a tragedy be a bildungsroman?

The first question asks a student to retrieve info from long-term memory. The second requires students to recall information — and to do mental work with it: they organize and integrate the parts of those definitions.

For that reason, I think of retrieval practice as an early-in-the-learning-process question. Generative learning comes later in the process — that is, after students have relevant ideas in long-term memory to select, organize, and integrate.

The Ensers’ book explores research into, and practical uses of, several generative learning strategies: drawing, mind-mapping, summarizing, teaching, and so forth.

In my thinking, those distinct sub-categories are less important that the overall concept. If students select, organize, and integrate, they are by definition answering generative learning questions.

For instance: the question “can a tragedy be a bildungsroman” doesn’t obviously fit any of the generative learning categories. But because it DOES require students to select, organize, and integrate, I think it fits the definition.

(I should fess up: technically, retrieval practice is considered a generative learning strategy. For the reasons described above, I think it’s helpful to use RP early in learning, and generative learning later in learning. My heresy could be misguided.)

“Generative learning” is a BIG category; teachers can prompt students to think generatively in all sorts of ways. A recent review by Garvin Brod suggests that some strategies work better than others for different age groups: you can check out those guidelines here.

TL;DR

In most school systems, teachers must ask some kind of summary questions (tests, projects) at the end of a unit. Such questions — if well designed — can benefit both teachers and students.

After students have a bedrock of useful knowledge and before we get to those final test/project questions, teachers should invite students to engage in generative learning. By selecting, organizing, and reintegrating their well-established knowledge, students solidify that learning, and make it more flexible and useful.

Brod, G. (2021). Generative learning: Which strategies for what age?. Educational Psychology Review, 33(4), 1295-1318.

* Grammar nerds: if you’re wondering why I wrote “Zoe and Mark Enser’s book” instead of “Zoe and Mark Ensers’ book” — well — I found that apostrophe question a stumper. I consulted twitter and got emphatic and contradictory answers. I decided to go with the apostrophe form that makes each Enser and invidivual — because each one is. But, I could be technically wrong about that form.