Today’s guest post is by Jim Heal, Director of New Initiatives, and Rebekah Berlin, Senior Program Director at Deans for Impact.

Long-time readers know how much I respect the work that Deans for Impact does. Their Resources — clear, brief, research informed, bracingly practical — offer insight and guidance in this ever-evolving field.

Ask any teacher to name a rare commodity in their profession and there’s a good chance they will reply with the word: “Time.” Whether it’s time to plan, grade, or even catch one’s breath in the midst of a busy school day, time matters.

Time is perhaps most important when it comes to time spent focusing on the material you want students to learn. So, how do you ensure that you’re making the most of the time you have with students and that they’re making the most of the way you structure their time?

Water Is Life

To answer this, let’s consider the following scenario. You’re a 7th Grade ELA teacher teaching a lesson on ‘Water is Life’ – a nonfiction text by Barbara Kingsolver. One of the objectives for this lesson is: Analyze the development of ideas over the course of a text.

You know from reading the teacher’s guide that student success will require them to compare two parts of the reading: a section describing a lush setting with an abundance of water and another describing an arid setting where rain hardly ever falls. Comparing the two will allow students to explore one of the main ideas of the text: The environmental role played by water and water sustainability.

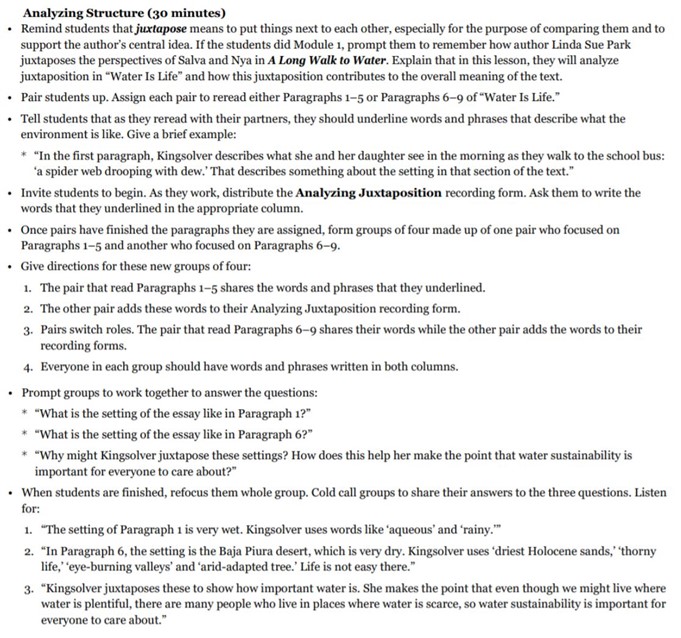

Here is the section of the lesson[1] designed to address these aims. Take a moment to read it and consider when students are being asked to think deeply about comparing the two settings:

You arrive at school on the morning you’re due to teach this content, and there’s an unexpected announcement for students to attend club photo sessions for the yearbook during your lesson.

Big Changes, Little Time

At this point you realize that, by the time your class gets back together, you’ll need to cut ten minutes from this part of the lesson and now you have a choice to make:

If you only had twenty minutes to teach the thirty minutes of content you had planned for, how would you adapt your plan so that the most important parts of the lesson remained intact?

Let’s begin addressing this challenge with a couple of simple truths:

First: The harder and deeper we think about something, the more durable the memory will be. This means that we need students to think effortfully about the most important content in any lesson if we want it to stick.

Second: If you treat everything in the lesson as equally valuable and try to squeeze it all into less time, students are unlikely to engage in the deep thinking they need to remember the important content later.

Therefore, something’s got to give.

To help determine what goes and stays, you’re going to need to differentiate between three types of instructional tasks that can feature in any given lesson plan.

Effortful Tasks

Tasks and prompts that invite students to think hard and deep about the core content for that lesson.

In the case of ‘Water is Life’ a quick review of the plan tells us the effortful question (i.e. the part that directs students to the core knowledge they will need to think deeply about) doesn’t come until the end of the allotted thirty minute period.

This question is this lesson’s equivalent of the ‘Aha!’ moment in which students are expected to “analyze the development of ideas over the course of the text” (the lesson objective) by exploring the way the author uses juxtaposition across the two settings.

If you reacted to the shortened lesson time by simply sticking to the first twenty minutes’ worth of content, the opportunity for students to engage in the most meaningful part of the lesson would be lost. It’s therefore crucial to ask what is most essential for student learning in each case and ensure that those parts are prioritized.

Essential Tasks

Foundational tasks and prompts that scaffold students to be able to engage with the effortful questions that follow.

Just because effortful thinking about core content is the goal, that doesn’t mean you should make a beeline for the richest part of the lesson without helping students build the essential understanding they will need in order to engage with it effortfully.

In the case of ‘Water is Life’ – even though some of the tasks aren’t necessarily effortful, they are an essential stair step for students to be able to access effortful thinking opportunities.

For example, consider the moment in the lesson immediately prior to the effortful thinking prompt we just identified:

As you can see, even though we want students to go on and address the effortful task of juxtaposing the language in each of the two settings, that step won’t be possible unless they have a good understanding of the settings themselves. This part might not be effortful, but it is essential.

In this example, it isn’t essential that students share their understanding of each setting as stated in the plan, but it is essential that they do this thinking before taking on a complex question about juxtaposed settings. In other words, the instructional strategy used isn’t essential, but the thinking students do is.

Armed with this understanding, you can now shave some time off the edges of the lesson, while keeping its core intentions intact. For instance, in a time crunch, instead of having groups work on both questions the teacher could model the first paragraph and have students complete the second independently.

Strategies like these would ensure students engage more efficiently in the essential tasks – all of which means more time and attention can be paid to the effortful task that comes later on.

Non-Effortful, Non-Essential Tasks

Lower-priority tasks and prompts that focus on tangential aspects of the core content.

Lastly, there are those parts that would be nice to have if time and student attention weren’t at a premium – but they’re not effortful or essential in realizing the goals of the lesson.

If your lesson plan is an example of high-quality instructional materials (as is the case with ‘Water is Life’) you’ll be less likely to encounter these kinds of non-essential lesson components. Nevertheless, even when the lesson plan tells you that a certain section should take 30 minutes, it won’t tell you how to allocate and prioritize that time.

This is why it’s so important to identify any distractions from the ‘main event’ of the lesson. Because effortful questions are just that: they are hard and students will need more time to grapple with their answers and to revise and refine their thinking – all of which can be undermined by non-essential prompts.

For instance, it might be tempting to ask…

…“What was your favorite part of the two passages?”

…“What does water sustainability mean to you?”

…“Has anyone ever been to a particularly wet or dry place? What was it like?

These might seem engaging – and in one definition of the term, they are – it’s just that they don’t engage students with the material you want them to learn. For that reason alone, it’s important to steer clear of adding questions not directly related to your learning target in a lesson where you’re already having to make difficult choices about what to prioritize and why.

Three Key Steps

It’s worth noting that, even though our example scenario started with a surprise announcement, this phenomenon doesn’t only play out when lesson time gets unexpectedly cut. These kinds of decisions can happen when you know your students will need more time to take on an effortful question than the curriculum calls for, or even when lesson time is simply slipping away faster than you had anticipated. In either case, you would need to adjust the pacing of the lesson to accommodate the change, and bound up within that would be the prioritization of its most important parts.

There are steps one can take to ensure the time you have becomes all the time you need. Here are three such strategies informed by Deans For Impact’s work supporting novice and early-career teachers:

Identify the effortful tasks – aka the opportunities for effortful thinking about core content within the lesson. These effortful ‘Aha!’ moments can appear towards the end of the lesson, so don’t assume that you can trim content ‘from the bottom up’ since that could result in doing away with the most important parts for student learning.

Determine which are the essential tasks – aka the foundational scaffolds students will need in order to engage with those effortful thinking opportunities. These stepping stone tasks will often deal with the knowledge and materials students need to engage in the effortful part of the lesson. Even though they can’t be removed, they can be amended. If in doubt, concentrate on the thinking students need to do rather than the surface features of the instructional strategy.

Trim those parts of the lesson that don’t prompt effortful thinking or the foundational knowledge required to engage in it. This means that anything NOT mentioned in the previous two strategies is fair game for shrinking, trimming or doing away with altogether. Ask yourself whether this part of the lesson is instrumental in getting students to engage deeply with the content you want them to take away.

So, even if lesson time always feels like it’s running away (which it often is!) there are steps we can take to ensure teachers (and subsequently students) make the most of it.

Jim Heal is Director of New Initiatives at Deans for Impact and author of ‘How Teaching Happens’. He received his master’s in School Leadership and doctorate in Education Leadership from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Rebekah Berlin is Senior Director of Program at Deans for Impact. She received her Ph.D. in teaching quality and teacher education from the University of Virginia.

If you’d like to learn more about the work of Deans for Impact, you can get involved here.

[1] “Grade 7: Module 4B: Unit 1: Lesson 1” by EngageNY. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

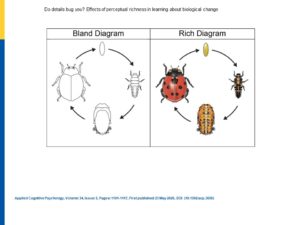

![“Rich” or “Bland”: Which Diagrams Helps Students Learn Deeply? [Reposted]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/AdobeStock_252915030_Credit.jpg)

![To Grade or Not to Grade: Should Retrieval Practice Quizzes Be Scored? [Repost]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/AdobeStock_288862877_Credit.jpg)

![Making “Learning Objectives” Explicit: A Skeptic Converted? [Reposted]](https://www.learningandthebrain.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/AdobeStock_264152189_Credit.jpg)