Over at the Blog on Learning and Development, they’ve penned a dramatic headline: Exams May Damage Teenagers’ Mental Health and Restrict Their Potential.

Damage mental health.

Restrict teenagers’ potential.

That’s got your attention.

Your response to such a headline might well depend on your current beliefs about exams.

If you already think that exams harm students, you might cry out a triumphant “I told you so!” You might send a link to your principal, along with a proposal to cancel the lot of them.

If you already think that exams hold students (and teachers) beneficially accountable for the information and skills they ought to have mastered, you might dismiss the blog post as yet another refusal to maintain strict but helpful standards.

I have an alternate suggestion:

Don’t take sides.

Instead, ask yourself a reasonable and straightforward question:

What pertinent evidence does the blog post offer to support its claims?

After all, you’ve decided to join Learning and the Brain world because you want to go beyond opinions to arrive at research-informed opinions.

So, as you review the blog post beneath that dramatic headline, don’t look for statements you agree (or disagree) with. Instead, check out the quality of the evidence provided in support.

Which Door?

Let’s start by asking this question: which kind of evidence would you find most persuasive?

A survey of high school principals, focusing on student stress levels.

A study comparing the mental health of students who took exams to the health of those who didn’t.

An online poll of high school students and their parents, asking about the highs and lows of high school.

An opinion piece by a noted neuroscientist.

A survey of therapists who work with teens.

Presumably, given these choices, you’d prefer door #2: the research study.

In this hypothetical study, researchers would identify two similar groups of adolescent students. One group would take exams. The other wouldn’t.

When researchers evaluated these students later on, they would find higher rates of mental health diagnosis in the exam group than the no-exam group. (For a relevant parallel, check out this study on developing self-control.)

Such a study would indeed suggest–as the blog states–that “exams may damage teenagers’ mental health.”

The other methods would, of course, reveal opinions. Those opinions might well be informed by different kinds of experience: the students’ experience, their parents’, their teachers’, their therapists’.

But, even well-informed opinions can’t root out the biases that well-designed research seeks to minimize.

Let the Sleuthing Begin

As you begin reviewing this blog post, you’ll find several links to research studies. That’s a good sign.

However–and this is a big however–those cited studies don’t investigate the blog’s central claim. That is: they don’t explore the effects of exams on teens.

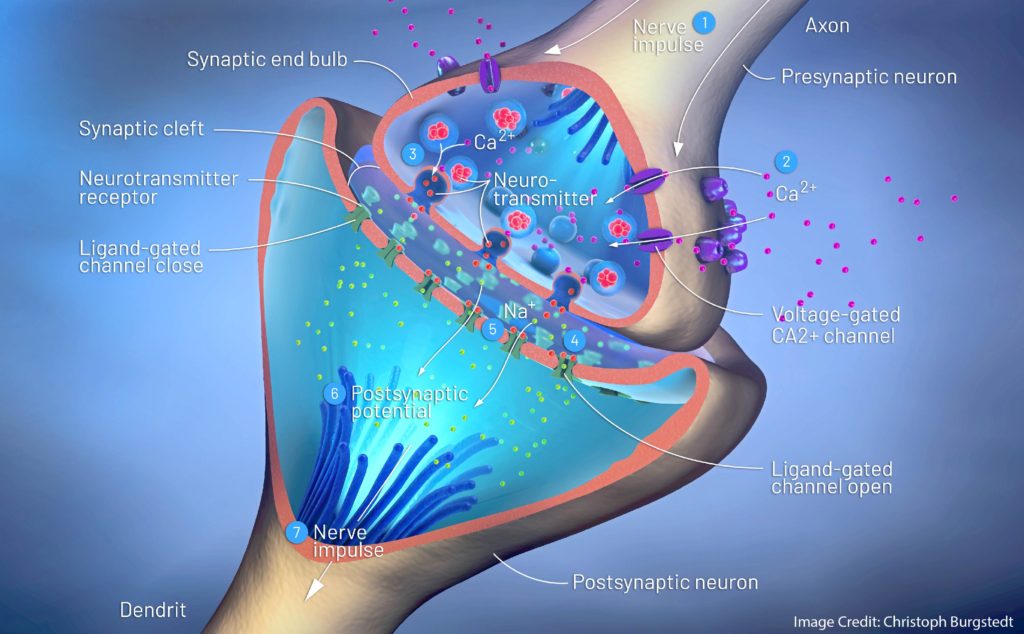

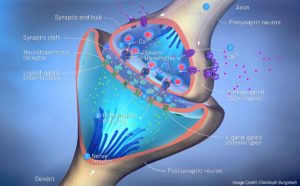

Instead, they offer evidence that adolescence is an important time for neuro-biological development. That’s true and important, but it’s not the blog post’s central claim.

Once the author has developed the (important and true) claim that brains change a lot in adolescence, the blog arrives at its core assertion: “GSCEs [exams] impose unnecessary stress on adolescents.”

To support that claim, it offers this link.

Credible Sources

This link reveals good news, and bad.

Good News: the argument that “exams might damage teens’ mental health” comes from a newspaper article covering a neuroscientist’s speech. That scientist–Sarah-Jayne Blakemore–has done lots of research in the world of adolescent brains. She does splendid work.

In fact her most recent book, Inventing Ourselves, has been enthusiastically reviewed on this blog. Twice.

Bad News: the concern that exams might damage mental health is Blakemore’s (very well informed) opinion–but it’s an opinion. She’s giving a speech, not describing a study.

The hypothetical study outlined above–the one that was your first choice for evidence–hasn’t been done. (More precisely: it’s not cited by the blog, or by Blakemore.)

More Bad News: when Blakemore says that “exams” might damage mental health, she means very specific exams: the General Certificate of Secondary Education exams–a kind of a mandatory SAT exam in Great Britain.

That is: Blakemore does not say that exams in general harm students. Despite the headline, nothing in this article even indirectly suggests that schools shouldn’t have final exams.

If you want to persuade your principal to cancel all exams, this article simply doesn’t help you make that case.

Back to the Beginning

Let’s return to the blog headline that got us started: Exams May Damage Teenagers’ Mental Health and Restrict Their Potential.

I think this headline sets up a reasonable expectation. I expect (and you should too) that researchers have done a relevant study, crunched some numbers, and arrived at that conclusion.

They don’t just have an opinion. They don’t just have relevant expertise. They’re not making a prediction.

Instead, they have gathered data, controlled for variables that might muddle their conclusion, done precise calculations, and arrived at a statistically significant finding.

In the absence of that study, it’s genuine surprising that a blog (for an organization that champions brain research) has made such an emphatic claim.

Important Notes

First: I don’t know if the blog-post’s author wrote the headline. Often those two jobs fall to different people. (In newspapers especially, that arrangement can lead to misunderstanding and exaggerated claims.)

While I’m at it, I should also acknowledge that I myself might be guilty of an occasional hyperbolic headline.

I try to stick to the facts. I try (very hard) to cite exactly relevant research. I try to limit my claims to the narrow findings of researchers.

If you catch me going beyond these guidelines, I hope you’ll let me know.

Second: You might reasonably want to know my own opinions about exams. Here goes:

I haven’t seen any research that persuades me one way or the other about their utility.

I suspect that, like so many things in education, they can be done very badly, or done quite well.

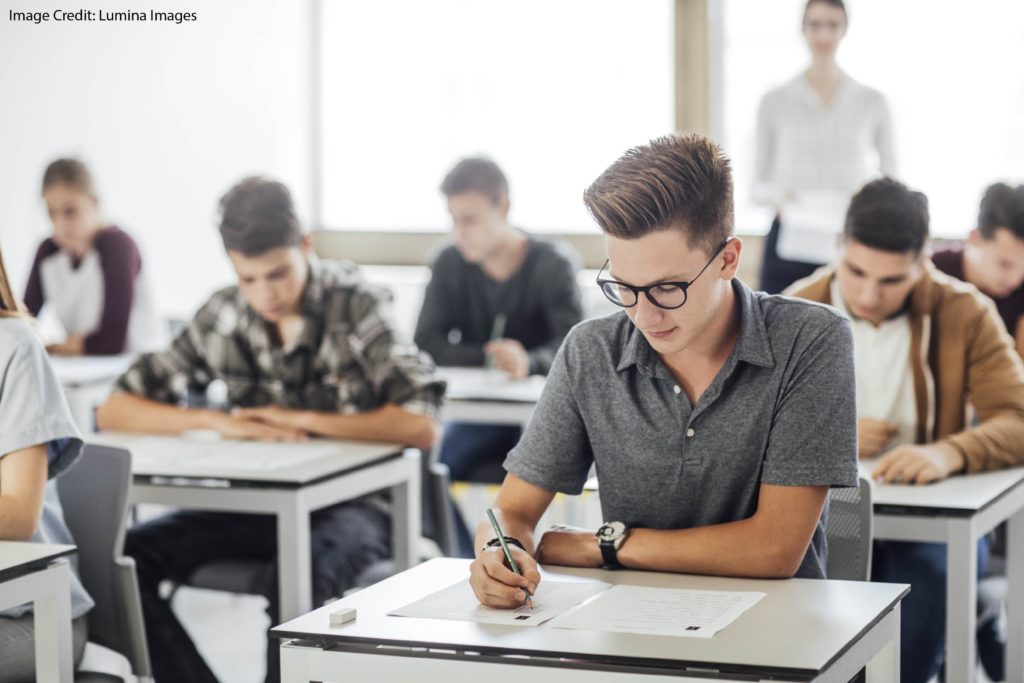

Can exams become hideous exercises in mere memorization, yielding lots of stress but no extra learning? Yes, I’m sure that happens.

Can exams be inspiring opportunities for students to show their deep mastery of complex material? Yes, I’m sure that happens.

As is so often the case, I think global conclusions (and alarming headlines) miss the point.

We should ask: what kind of learning we want our students to do? What kind of learning climate we want to create? And, we should ask what kind of exam–including, perhaps, no exam at all–produces that result for most of our students.