You’ve seen the videos.

An earnest reporter wielding a microphone accosts a college student and asks extremely basic questions:

“What are the three branches of government?”

“What is the capital of France?”

“Who wrote the Declaration of Independence?”

When students can’t answer these questions, the reporter eyes the camera wryly, as if to say, “What’s wrong with Kids These Days?”

One such video made the rounds recently. Middle schoolers (I think) didn’t know what D-Day was: they hypothesized he might be a rapper.

So, really: what is wrong with these kids? How can they POSSIBLY not know about D-Day?

Beyond History

Our lament frequently goes beyond students’ lack of historical knowledge.

We worry about “kids and their devices.”

They’re always looking at screens! (I’m here to tell you: back in the ’80s, we never looked at screens.)

They’re always texting! (We never texted.)

They’re so distractible! (Nope. Not us.)

If students know so little and concentrate so badly, we have to wonder what’s up with them.

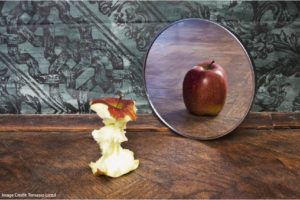

Distateful Mirrors

I understand the frustration. (I’ve taught a class of well-educated students who didn’t know the story of Noah’s Ark. That was a shocker.)

At the same time, I think that question distracts us from the essential underlying point.

If an entire room of students didn’t know what D-Day was, it’s clear that the school system didn’t teach them about D-Day; or — at least — that didn’t teach them well enough for them to consolidate that knowledge.

If we can easily find college students who don’t know from geography and history, we can blame the college students. But I think we should first pause to consider the education system in which it’s possible to complete high school without enduring knowledge of such things.

It is, in my view, simply not fair or helpful to blame students for being in the system that adults created.

Those videos shouldn’t make us condemn the students; they should instead make us look in the mirror.

We might not like what we see. But: their shortcomings tell us more about our education system than about our students.

The Ingenious Tech Switcheroo

The same argument, in my view, applies to laments about technology. Notice the impressive blame-shifting here:

Step 1: technology companies invent a must-have gadget. They market it to — say — 10 year olds.

Step 2: 10-year-olds want the gadget, and pester their parents to buy it. (The tech company doesn’t need to get money from adults; they persuade children to get money from their parents and give it to the company. BRILLIANT!)

Step 3: the tech industry then highlights the narrative that the 10-year-olds are to blame for being distractible. The problem is not in the adults’ behavior; it’s in the children! “Why oh why can’t these kids focus!”

Here again, the students’ behavior gives us essential feedback about adults.

If we want today’s students to concentrate better, maybe we should create — and provide them with — fewer distractions. Perhaps we should model the behavior we want to see. (Quick: how many browser tabs do you have open?)

Caveats, Always Caveats

One: not everyone worries when students don’t know stuff. (I do, but some don’t share that concern.) For adults who don’t emphasize factual knowledge, those videos seem trivial, not alarming.

Two: not all the data suggest that students are “more distractible.” Perhaps they simply have more distractions. (How many times did you check your cell phone in the last hour?)

Three: Of course, students bear responsibility for working effectively within the systems adults create. If twenty-four of my students learn something and one doesn’t, we can reasonably wonder what’s going on with that one. But, if none of my students know the importance of the Treaty of Versailles, I should think about the adult-driven systems, not “what’s up with kids these days.”

Four (this is a biggie): As I strive refocus popular outrage away from the students and toward the system in which they learn, I might seem to be blaming teachers and school leaders. I very much don’t mean to do that.

In my experience, the great majority of both groups work extremely hard, and do so with the best intentions. (Few people say: “I went into teaching to become rich.”)

At the same time: our well-intentioned efforts simply aren’t producing the results we want. That feedback — evident in those videos — should prompt honest and searching self-reflection.

In Sum

I promised a (partial) defense of ignorance and distractibility. Here goes:

Of course we want our children to know important information and skills, and to be able to concentrate on them.

If most students don’t and can’t, the fault probably lies with the education system, not children who learn within it.

Children who don’t know what D-Day is don’t deserve to be ridiculed on Twitter. They do deserve a curriculum that fosters knowledge, skill, and concentration. They deserve pedagogy that helps them master all three.

At Learning and the Brain, we connect education with psychology and neuroscience in order to start conversations. Conversations that include those three perspectives can help create such a curriculum; can help foster such pedagogy.

We hope you’ll join us!