In our profession, memorization has gotten a bad name.

The word conjures up alarming images: Dickensian brutes wielding rulers, insisting on “facts, facts, facts!”

In a world when students “can look up anything on the interwebs,” why do we ask students to memorize at all?

One answer from cognitive science: we think better with information we know well.

Even when we can find information on the internet, we don’t use that information very effectively. (Why? Working memory limitations muddle our processing of external information.)

A second answer appears in intriguing recent research.

Reasonable Plans, Unstated Assumptions

As a classroom teacher, I might operate on this reasonable plan:

Step one: we discuss ideas and information in class.

Step two: students write down the important parts.

And, step three: when students need that information later, they look at their notes.

This plan — the core of most high school classes I know — relies on unstated assumptions:

Assumption one: students’ notes are largely correct.

Assumption two: if students write down information INcorrectly, they’ll recognize that mistake. After all, we discussed the correct information in class.

But what if that second assumption isn’t true?

What if students trust external information (their notes) more than internal information (their memories)?

Assumptions Thwarted

In 2019, Risko, Kelly, & Gaspar studied one version of this question.

They had students listen to word lists, and type them into a storable file. After distraction, students got to review their lists. They then were tested on those words.

On the final list, however, these scholars did a sneaky thing: they added a word to the stored list. Sure enough, 100% of their students wrote down the additional word, even though it hadn’t in fact been on the initial word list.

Students trusted their written document (external “memory”) more than their own actual memory. When tested even later, students still included the additional word, even though it wasn’t a part of their initial learning.

In other words: the “reasonable plan” that teachers often rely on includes an assumption that — at least in this research — isn’t true.

Ugh.

Classroom Implications

This research, I think, reminds us that the right kind of memorization has great value for students.

We want students to know certain bedrock facts and processes with absolute certainty. We want them, for instance, to define key terms and ideas fluently. Crucially, we want them to reject — with confidence borne of certain knowledge — inaccurate claims.

For instance:

I just completed a unit on tragedy. My sophomores read August Wilson’s Fences and Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

On the very first day of the term, I went over a four-part definition of “tragedy.” (It’s a quirky definition, I admit, but it works really well.)

We reviewed that definition almost daily, increasingly relying on retrieval practice. For instance, I might give them this handout to fill in. Or we might do that work together on the board.

Over time, I started including inaccurate prompts in my questions: “So, tragedy ends in death or marriage, right?”

By this point, my students knew the definition so well that they confidently rejected my falsehoods: “No, you’re trying to trick us! Tragedy ends in death or banishment!”

For an even trickier approach, I encouraged students to correct one another’s (non-existent) mistakes:

Me: “T: what does comedy represent, and why?”

T: “The marriage (and implied birth) at the end of a comedy implies the continuity of society, and in that way contrasts tragedy’s death and banishment, which represent the end of society.”

Me: “M: what did T get wrong.”

M [confidently]: “Nothing. That was exactly right.”

Me [faking exasperation]: “S, help me out here. What did T and M miss?”

S [not fooled]: “Nothing. I agree with them both.”

Me: “Congrats to T for getting the answer just right. And congrats to M and S for not letting me fool you. It’s GREAT that you’re all so confident about this complex idea.”

Because these students knew this complex definition cold — because they had memorized it — they could stand firm when questioned skeptically. As a result, they did a great job when asked to apply that definition at the end of the term:

“How does Wilson’s Fences fit the definition of tragedy AND of comedy?”

To Sum Up

Despite all the bad press, the right kind of memorization can enhance learning.

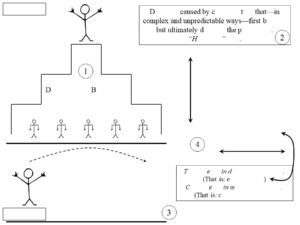

When students know foundational information and processes by heart, they

BOTH process questions more fluently

AND resist misleading information from “external memory” sources.

Greater cognitive fluency + greater confidence in their knowledge = enduring learning.