When I attended my first Learning and the Brain conference, more than a decade ago, I had a simple plan:

Step 1: Listen to the researcher’s advice.

Step 2: Do what the researcher told me to do.

Step 3: Watch my students learn more.

Step 4: Quietly glow in the satisfaction that my teaching is research-based.

In fact, I tried to follow that plan for several years. Only gradually did I discover that it simply couldn’t work.

Why?

Because researchers’ advice almost always applies to a very specific, narrow set of circumstances.

The teaching technique they use to help — say — college students learn calculus might not help my 10th graders write better Macbeth essays.

Or: their teaching strategy encourages a technology that my Montessori school forbids.

Or: research on American adolescents might not yield results that help teens raised in other cultures.

In other words: psychology and neuroscience research don’t provide me a handy checklist. I don’t just need to change what I do; I need to change how I think. I really wish someone had said to me:

“Before you change your teaching, change your thinking.”

Example the First

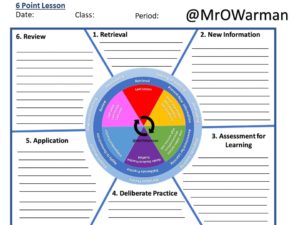

I thought of this advice when I saw a recent Twitter post by Otto Warman (@MrOWarman), a math teacher in Britain.

Warman has gone WAY beyond following a researcher’s checklist. Instead, he has synthesized an impressive amount of research, and reorganized it all into a lesson-planning system that works for him.

As you can see, his lesson plan form (which he has generously shared) prompts him to begin class with retrieval practice, then to introduce new information, then to check for understanding, and so forth. (You can click on the image to expand it.)

Each circle and slice of the diagram includes helpful reminders about the key concepts that he’s putting into action.

That is: he’s not simply enacting someone else’s program in a routinized way. He has, instead, RETHOUGHT his approach to lesson planning in order to use research-supported strategies most appropriately and effectively.

To be clear: I DO NOT think you should print up this sheet and start using it yourself. That would be a way to change what you do, not necessarily a way to change what you think. The strategies that he has adopted might not apply to your students or your subject.

Instead, I DO THINK you should find inspiration in Warman’s example.

What new lesson plan form would you devise?

Are there cognitive-science concepts you should prioritize in your teaching?

Will your students benefit especially from XYZ, but not so much from P, Q, or R?

The more you reorganize ideas to fit your particular circumstances, the more they will help your teaching and your students.

Example the Second

Over on his blog (which you should be reading), Adam Boxer worries that we might be making a mess of retrieval practice.

Done correctly, retrieval practice yields all sorts of important benefits. Done badly, however, it provides few benefits. And takes up time.

For that reason, he explains quite specifically how his school has put retrieval practice to work. As you’ll see when you review his post, this system probably won’t work if teacher simply go through the steps.

Instead, we have to understand the cognitive science behind retrieval practice. Why does it work? What are the boundary conditions limiting its effectiveness? How do we ensure that the research-based practice fits the very specific demands of our classes, subjects, and students?

Retrieval practice isn’t just something to do; it’s a way to think about creating desirable difficulty. Without the thinking, the doing won’t help.

To Sum Up

What’s the best checklist for explaining a concept clearly? There is no checklist: think differently about working memory and schema theory.

What’s the best daily schedule for a school? There is no best schedule: think differently about attention.

What steps help are most powerful to help students manage stress? Before we work steps, we have to think differently about students’ emotional and cognitive systems.

To-do lists are straightforward and easy. Teaching is complex and hard. Think different.