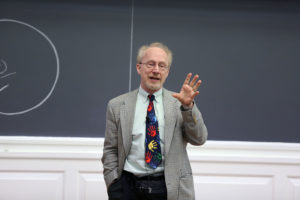

Professor Kurt Fischer changed my professional life. If you’re reading this blog, odds are good he helped change yours as well.

Throughout most of the 20th century, teachers, psychologists, and neuroscientists had little to say to one another.

Even psychology and neuroscience — two fields that might seem to have many interests in common — eyed each other suspiciously for decades. Certainly teachers weren’t a welcome part of any wary conversation that might take place.

As we all know, and Dr. Fischer helped us see, these fields have so much to learn from each other.

Today’s growing consensus that these disciplines — and several others — should be in constant conversation results in large measure from his insight, effort, generosity, and wisdom. So: he’s changed our lives, and greatly benefited our students.

Since I heard of his death, I’ve been thinking how Dr. Fischer’s great skill was to keep the bigger picture in mind. He did so in at least two essential ways.

Creating Interdisciplinary Institutions

Academic disciplines exist for good reasons. And yet — despite all the good that they do — they can create barriers and restrict conversations.

To foster inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary conversations, Dr. Fischer knew we needed institutional systems. In our field, he helped start all the essential ones.

He helped create the Mind, Brain, and Education strand at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. It was, I believe, the first such program in the world.

He helped found the International Mind Brain Education Society (Imbes.org), which works to “to facilitate cross-cultural collaboration in biology, education and the cognitive and developmental sciences.”

He helped found the Mind Brain Education Journal, which publishes vital interdisciplinary research.

And, of course, he helped organize the very first Learning and the Brain conference — to ensure that these conversations took place not simply in academic institutions, but with classroom teachers as well.

In starting all these institutions and starting all these conversations, Dr. Fischer created a generation of leaders — those who now champion the work we do every day.

That’s the bigger picture he could see from the beginning.

Understanding Brains in Context

Dr. Fischer saw the bigger picture in his teaching life as well.

As part of his work at Harvard’s School of Education, he taught a course on “Cognitive Development, Education, & the Brain.”

Over those weeks, he returned frequently to an especially damaging fallacy, which he called “brain in a bucket.”

That is, he wanted his students not to think about individual brains operating in some disembodied ether. Instead, he wanted us to think constantly about context:

How does the brain interact with the body?

In what ways is it shaped by development?

How do family interactions shape self? Social interactions? Cultural interactions?

How should we think about hormones, and about ethics, and about evolution, and about genetics?

In other words: neuroscience teaches us a lot about brains. But we should always think about the bigger picture within which that brain functions, and about the forces that created it in the first place.

Never focus on “a brain in a bucket,” because that brain makes no sense without the context that surrounds and shapes it.

In Conclusion

So for me, that’s Dr. Fischer’s legacy. He helped create the context that shaped so many of our brains:

Graduate programs in Mind, Brain, Education,

Learning and the Brain conferences (55 and going strong),

Professional associations and journals,

The scholars and conversations that inspire teachers and improve teaching.

The world is better because he lived, and a poorer place now that he’s gone. Happily for us, he left great wisdom and greater understanding behind.