Curiosity and Play: Snowflakes and Standards

by Dr. Debbie Donsky

Common themes ran throughout the Learning and the Brain conference in San Francisco, February 17-19, 2017 but the ones that resonated most strongly with me were the ideas of curiosity and play, and how they impact both learning and parenting. It makes sense that this should be the case given that I am a mother of two teenagers and an educator of almost 25 years.

Like most, I am drawn to the ideas that confirm my biases around learning. So much of what I have always believed can now be confirmed through brain science and not just my hunches! Some of these key beliefs include:

- Standardized tests don’t improve learning.

- Play and creativity are important at all ages.

- Parenting and teaching have a significant influence on both.

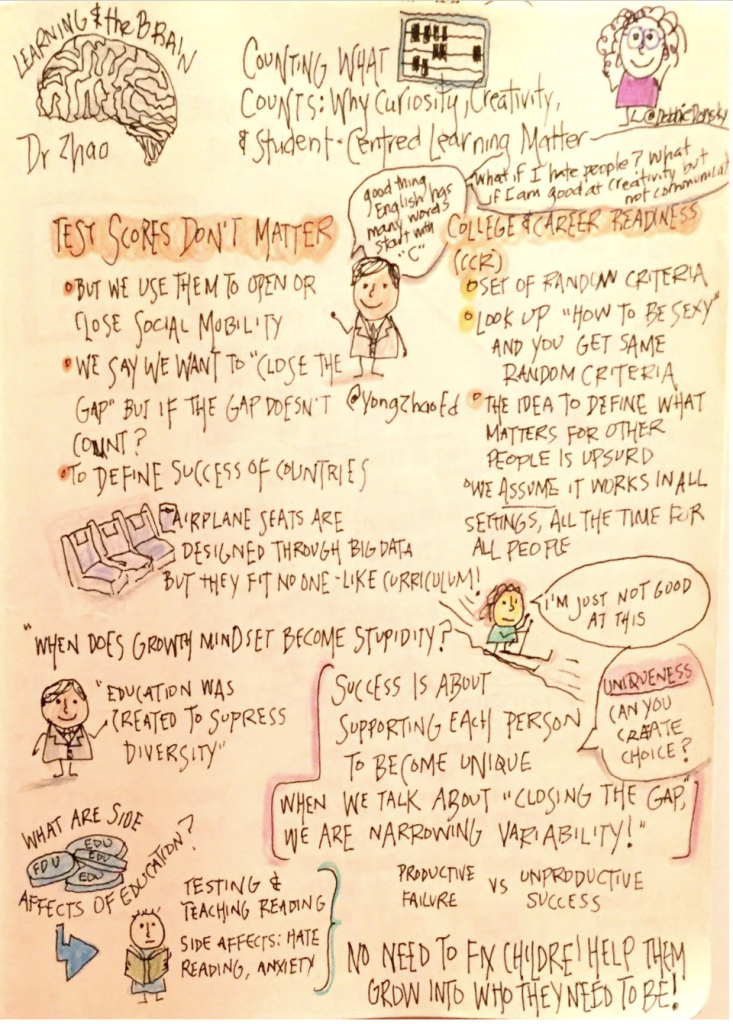

Yong Zhao in his keynote, Counting What Counts: Why Curiosity, Creativity and Student-Centred Learning Matter, argued that the goal of “closing the gap” sounds admirable, but paradoxically results in making everyone average.

He suggested that, ultimately, the role of education is to help our children become who they are meant to be instead of working towards an average which testing promotes.

He explained that we claim to want to “close the gap,” but then challenged us to consider that the gap itself doesn’t matter. After all, the tests that determine where the gaps exist, are flawed in the first place.

Zhao noted that we use these flawed tests to determine:

- the achievement of our children,

- the skill level of our educators and ultimately,

- the success of nations—

for instance, with the PISA test.

Yong Zhao explained that what we test is actually quite random; standardized tests evaluate students based on whatever success model is presently in vogue. We take this narrowed, biased model of success and try to replicate it in schools; yet these models further reduce diversity of thought, experience and creativity among our students.

(They also reduce diversity of thought among educators, who know that teaching to the test is the path of least resistance. )

Zhao’s clear message was, “success is about supporting each person to become unique. When we talk about closing the gap, we are narrowing the variability.” He fears that “education was created to suppress diversity” in a time when assembly lines were the prevailing job that workforce had.

If we are to support our children to become creative problem-solvers, then we need to move away from pursuing averages that are based on a single prescribed profile for all learners.

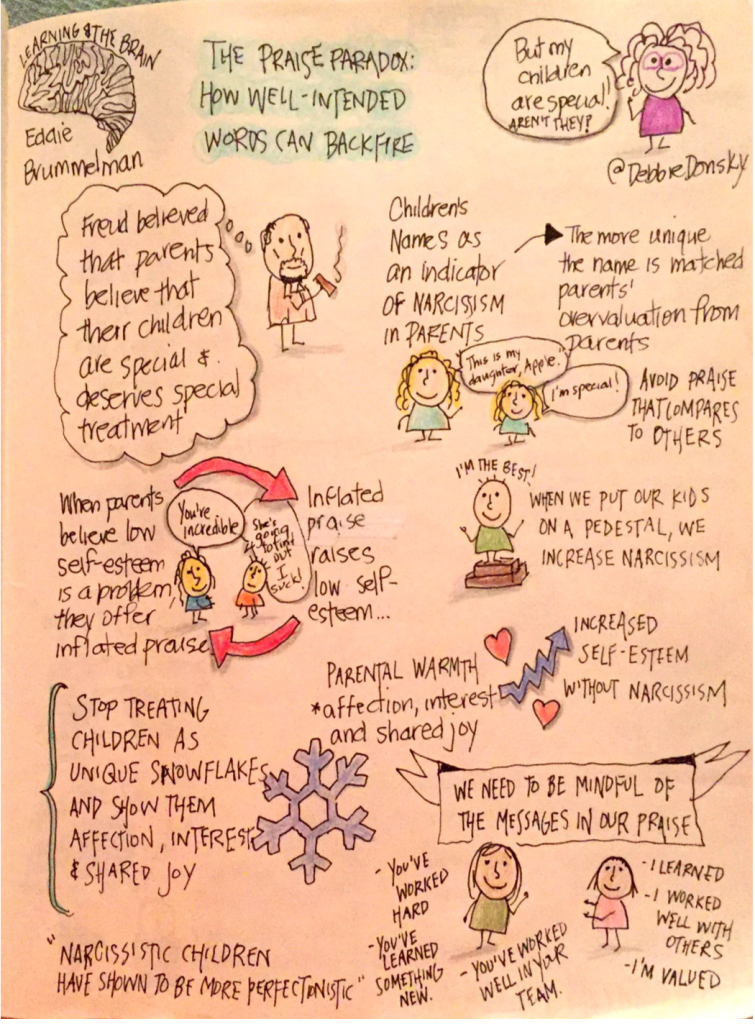

Eddie Brummelman’s message in his session, The Praise Paradox: How Well-Intended Words Can Backfire, was that we should not treat our children as “unique snowflakes”: an argument which initially seemed to contradict Zhao’s research–but, in fact, supports it.

At the core of Brummelman’s work was the belief that yes, of course, we can praise our children– but not in comparison to others.

The reason we praise our children should be the desire to support them in their growth. When praise is mixed with comparison to others, it confuses the message by implying that what makes the child special is related to others when in fact, it is only tied to the individual. So when we say, “You are a wonderful artist. I love the way you use colour to convey mood!” versus “You are a much better artist than _____!” Brummelman stresses that uniqueness relies on comparison but that praise should be connected to the child’s passions, interests and talents that will lead them towards their best selves.

In this way, Brummelman echoes Zhao’s argument. By creating norms and averages we are drawn to comparison and rank–rather than to our children’s curiosities about what they want to learn, become or aspire to be.

Brummelman’s research cautions parents against overpraising our children, lest we lead them to narcissism and entitlement. It isn’t that we should avoid praise, but that certain types of praise are more effective in raising children to be successful, functioning adults.

Specifically, he explained that when parents believe their children are struggling with low self-esteem, they tend to overpraise–believing that extra praise will in fact raise the child’s self esteem. But, his research showed that it does the opposite. Children with praise-boosted narcissism tend to be more perfectionistic. They seek more praise and therefore fear risks; in other words, they are less likely to embrace play and creativity.

If praise is tied to the child’s perception of success, and success is tied to narrow definitions of achievement, then children work towards that common standard against which Zhao cautioned us. If they are less likely to take risks then they will seek a single right answer rather than embrace both creativity and curiosity. The standardized test will always be the measure of success.

Brummelman explained that what has the most profound impact on our children is the experience of parental warmth, interest and shared joy. They don’t need praise–they need our presence and affection. Zhao stresses that as educators and parents we must guide and nurture our children and students so that they can grow into the unique people they are meant to become.

This complexity draws me to think about the scene in Pixar’s movie, The Incredibles, when Dash is being scolded for running too fast in a race. He is frustrated because he wants to engage with his superpowers but it isn’t safe, in the climate they live in, to let others know about their powers:

Mom explains to her son , “The world just wants us to fit in and to fit in, we just gotta be like everyone else.”

Dash challenges her with a “ya, but” as many kids do, “But dad always said our powers were nothing to be ashamed of–our powers made us special!”

His mother tells him, her frustration obvious from her tone, “Everyone is special, Dash…”

He turns away to look out the window and replies, “Which is another way of saying no one is…”

Of course, Dash’s mom is doing this to protect him and her other children.

In other words, like Dash, we all have super powers, and as Dash’s mom stresses, we stay in our space of trying to fit in and be like everyone else because it is safer in many ways. When the time is right and she realizes the importance of her children’s powers, she encourages both Dash and his sister to use them.

When Dash is discouraged from standing out, he is falling in line with the average that Zhao argues is the problematic goal of education. When he moves out of the space and engages with his powers, it connects us to the ideas of Brummelman, who sees these powers as self expression and self actualization.

As a system leader, I understand how deeply important for us to consider what both Zhao and Brummelman are saying about the role of assessment, praise and student success.

I have taken their ideas and informed my own understanding of the vital role of assessment, reporting to parents and school/system improvement as a whole. I have made a commitment to question the status quo and the acceptance of average as the goal to ensure that our students are supported in finding who they are as creative and curious learners.

If you would like to see the sketchnotes and comments for all the keynotes and presentations I attended, you can see more of my thoughts about the conference here.

[Editor’s Note: Dr. Debbie Donsky is Principal of Curriculum and Instruction Services, Learning Design & Development, and the Arts, at the York Region District School Board in Ontario, CA. You can follow her on Twitter: @DebbieDonsky]