Who are you without your memory?

Who are you without your memory?

In neurobiological lingo: who are you without your hippocampus?

The Best-Known Answer

No doubt you’ve heard of Henry Molaison, aka H. M., whose hippocampi were removed in order to cure debilitating epilepsy.

The good news: the operation (more-or-less) fixed the epilepsy.

The (very) bad news: without his hippocampi, Henry couldn’t form new long-term memories. In fact, he struggled to recall prior memories as well.

So much of our knowledge about memory formation comes from Henry’s life.

We understand the brevity of working memory because of H. M.

We distinguish between declarative memory (“knowing what”) and procedural memory (“knowing how”) better because of H. M.

As Suzanne Corkin describes in Permanent Present Tense, research into Henry’s very rare brain tells us more about each of our brains.

Today’s News: A New Henry

On December 29 of 2007, artist Lonni Sue Johnson came down with a bad case of viral encephalitis. As a result, she ended up with severe damage to both her hippocampi. This damage, in fact, resembles H.M.’s surgical lesions.

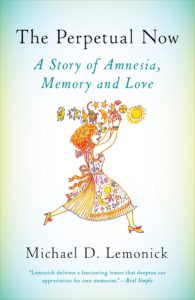

You can read about her case in a remarkable book by Michael D. Lemonick, The Perpetual Now: A Story of Amnesia, Memory, and Love.

Lonni Sue’s situation resembles Henry’s in many ways — they both live in a “perpetual now” — but their stories differ as well.

First: Henry was relatively young at the time of his surgery, and so he hadn’t yet developed professional skills. (Because his epilepsy also proved quite debilitating, he didn’t get very far in school.)

Lonni Sue, however, was an accomplished artist and musician — even an amateur pilot.

For example: she drew several covers for the New Yorker magazine. You might recognize her whimsical style if you google her art.

Second: Her family decided soon after her illness that they would be as public as Henry’s family had been private. They want her remarkable condition — as much as possible — to benefit science, and the public’s understanding of the brain.

For that reason, when Lonni Sue’s sister Aline ran into Lemonick on the street, she asked if he wanted to write about her life without memory.

Third: Lonnie Sue brought a remarkable good cheer to a life that might seem so depressing, even terrifying, to others.

When Lemonick first met her, she brightly introduced herself and showed him her drawings. Then, she introduced him to a word game she often played: “singing the alphabet.”

She sang a list of words that grew in alphabetical order. Here’s what she sang that first time (and, notice how cheerful the words are!):

“Artists beautifully creating delightful exquisite finery giving hospitable inspiration joining keen laughter’s monthly necessities openly preparing quiet refreshment sweetly turning under violet weathervane xylophones yearning zestfully”

Life Without Memory: Research Findings

For the same reasons that Aline invited Lemonick to write about her sister, she has also invited researchers to learn what they can from Lonnie Sue’s brain.

Lemonick does a wonderful job of explaining these research findings. He does go into the methodological details. But he maintains a big-picture emphasis on the history and meaning of the research.

For instance, we saw that research on Henry helped solidify a distinction between procedural and declarative memory. Further research with Lonni Sue suggests that these categories often overlap.

Her knowledge of music, for example, acts like both declarative and procedural knowledge at the same time.

For teachers, this finding just makes sense.

So many of the skills students learn require them to know facts AND procedures. A chemistry lab, a historical investigation, a business plan: all these school accomplishments ask students to know stuff, and to do things with that knowledge.

The Perpetual Now won’t necessarily help classroom teachers design better lesson plans. But, it does help us understand the rich complexity of human memory.

And, it tells the story of an extra-ordinary life: one where “xylophone weathervanes yearn zestfully.”

I recommend the book enthusiastically.