Retrieval Practice is all the rage these days — for the very excellent reason that it works.

Study after study after study suggests that students learn more when they pull information out of their brains (“retrieval practice”) than by putting information back into their brains (“mere review”).

So, teachers naturally want to know: what specific teaching and studying strategies count as retrieval practice?

We’ve got lots (and lots) of answers.

Flashcards — believe it or not — prompt retrieval practice.

Short answer quizzes, even if ungraded. (Perhaps, especially if ungraded)

Individual white boards ensure that each student writes his/her own answer.

So, you can see this general research finding opens many distinct avenues for classroom practice.

Retrieval Grids: The Good

One strategy in particular has been getting lots of twitter love recently: the retrieval grid.

You can quickly see the benefits.

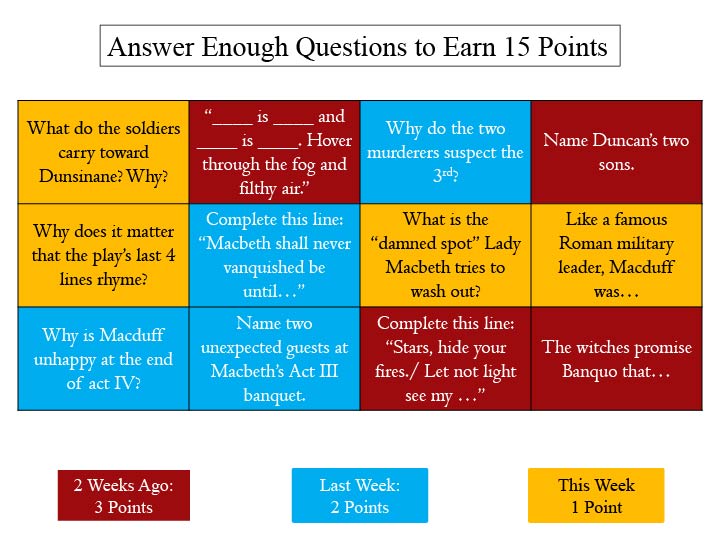

In the retrieval-grid quiz below, students answer short questions about Macbeth. Crucially, the grid includes questions from this week (in yellow), last week (in blue), and two weeks ago (in red).

Because students get more points for answering older/harder questions, the form encourages retrieval of weeks-old information.

So much retrieval-practice goodness packed into so little space. (By the way: this “quiz” can be graded, but doesn’t need to be. You could frame it as a simple review exercise.)

Retrieval Grids: My Worries

Although I like everything that I’ve said so far, I do have an enduring concern about this format: the looming potential for working memory overload.

Students making their way through this grid must process two different streams of information simultaneously.

In part of their working memory, they’re processing answers to Macbeth questions.

And, with other parts of their working memory, they’re processing and holding the number of points that they’ve earned.

And, of course, those two different processing streams aren’t conceptually related to each other. One is Macbeth plot information; the other is math/number information.

As you know from my summer series on working memory, that’s a recipe for cognitive overload.

Retrieval Grids: Solutions?

To be clear: I’m not opposed to retrieval grids. All that retrieval practice could help students substantially.

I hope we can find ways to get the grid’s good parts (retrieval practice) without the bad parts (WM overload).

I don’t know of any research on this subject, but I do have some suggestions.

First: “if it isn’t a problem, it isn’t a problem.” If your students are doing just fine on retrieval grids, then obviously their WM isn’t overwhelmed. Keep on keepin’ on.

But, if your students do struggle with this format, try reducing the demands for simultaneous processing. You could…

Second: remove the math from the process. Instead of requiring 15 points (which requires addition), you could simply require that they answer two questions from each week. You could even put all the week-1 questions in the same row or column, in order to simplify the process. Or,

Third: include the math on the answer sheet. If they write down the points that they’ve earned at the same time they answer the question, they don’t have to hold that information in mind. After all, it’s right there on the paper. So, a well-designed answer sheet could reduce WM demands.

Fourth: no doubt, as you read this, you are already coming up with your own solutions. If you have an idea that sounds better than these — try it! (And, I hope you’ll share it with me.)

To Sum Up

Researchers work by isolating variables. Teachers and classrooms work by combining variables.

So: researchers who focus on long-term memory will champion retrieval practice and retrieval grids.

Researchers who focus on working memory might worry about them.

By combining our knowledge of both topics, we teachers can reduce the dangers of WM overload in order to get all the benefits of retrieval practice.

That’s a retrieval-grid win-win.