You read that right.

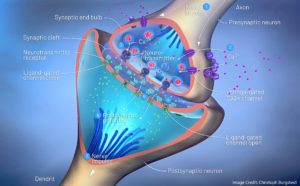

All those diagrams of synapses and neurotransmitters might be factually correct, but misinterpreted to explain memory formation.

Basically, some researchers argue that we’re thinking about learning in the wrong place. In the old model, we focused on many, many interactions at the very tips of the dendrites.

In a new model, the researchers propose we focus on a few changes at the root of the dendrites — much closer to the place where they connect to the neuron’s main body.

This summary explains the headlines. (The original article itself can be found here.)

Both these links include helpful visuals to understand the difference between these two models.

The details are fantastically complicated. But the possibility of a new model is…technically speaking…awesome sauce.

What Should Teachers Do With This New Knowledge?

Believe it or not, not much.

In the first place, we should remember that for teachers: neuroscience is fascinating, but psychology is helpful.

That is, we don’t really need to know exactly what changes in the brain when students learn. (Although, of course, it’s SO INTERESTING.)

But, we DO really need to know what teaching practices create those neural changes — whatever they might be.

We need to manage working memory load.

We need to help students manage their alertness levels.

And, we need to use retrieval practice.

And so forth.

In every case, psychology research tells us what teaching strategies do and don’t help. If — as might be true in this case — our neuro-biological understanding changes, that change almost certainly doesn’t matter to our teaching.

We still need to manage working memory and alertness.

We still need to use retrieval practice.

And so forth.

We might think differently about the neurons and synapses and dentrites, but we will keep using the most effective teaching practices.

In the Second Place…

Let this news remind us of Kurt Fischer’s famous saying: “when it comes to the brain, we’re all still in first grade.” That is: modern neuroscience is still a young discipline, and we’ve got LOTS more to learn.

So, we can indeed be thrilled by all the neuroscience information we glean at Learning and the Brain conferences. But, we shouldn’t latch onto it too firmly. Instead, we should expect that, as the years go by, our neuro-biological models will need several fresh revisions.

I have, in fact, waited over a year since this article was first published to see what traction it has gotten in the field. So far, I have heard almost nothing about it.

Simply put: I don’t know whether the new model is more accurate than the old. Perhaps, ten years from now, the old model will be seen as an embarrassing relic. Perhaps, instead, the new proposal will have been forgotten.

In either case, we can think more effectively about brains (and about teaching ad learning) if we keep our mental models flexible enough to allow for fresh discoveries.