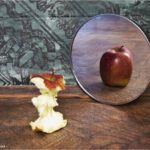

Here’s an interesting question: do students — on average — benefit when they repeat a grade?

As you contemplate that question, you might notice the kind of evidence that you thought about.

Perhaps you thought: “I studied this question in graduate school. The research showed that answer is X.”

Perhaps you thought: “I knew a student who repeated a grade. Her experience showed that the answer is X.”

In other words: our teaching beliefs might rest on research, or on personal experience. Almost certainly, they draw on a complex blend of both research and experience.

So, here’s today’s question: what happens when I see research that directly contradicts my experience?

If I, for instance, think that cold calling is a bad idea, and research shows it’s a good idea, I might…

… change my beliefs and conclude it’s a good idea, or

… preserve my beliefs and insist it’s a bad idea. In this case, I might…

… generalize my doubts and conclude education research generally doesn’t have much merit. I might even…

… generalize those doubts even further and conclude that research in other fields (like medicine) can’t help me reach a wise decision.

If my very local doubts about cold-calling research spread beyond this narrow question, such a conflict could create ever-widening ripples of doubt.

Today’s Research

A research team in Germany, led by Eva Thomm, looked at this question, with a particular focus on teachers-in-training. These pre-service teachers, presumably, haven’t studied much research on learning, and so most of their beliefs come from personal experience.

What happens when research contradicts those beliefs?

Thomm ran an online study with 150+ teachers-in-training across Germany. (Some were undergraduates; others graduate students.)

Thomm’s team asked teachers to rate their beliefs on the effectiveness of having students repeat a year. The teachers then read research that contradicted (or, in half the cases, confirmed) those beliefs. What happened next?

Thomm’s results show an interesting mix of bad and good news:

Alas: teachers who read contradictory evidence tended to say that they doubted its accuracy.

Worse still: they started to rely less on scientific sources (research) and more on other sources (opinions of colleagues and students).

The Good News

First: teachers’ doubts did not generalize outside education. That is: however vexed they were to find research contradicting prior beliefs about repeating a year, they did not conclude that medical research couldn’t be trusted.

Second: teachers’ doubts did not generalize within education. That is: they might have doubted findings about repeating a year, but they didn’t necessarily reject research into cold calling.

Third: despite their expressed doubts, teachers did begin to change their minds. They simultaneously expressed skepticism about the research AND let it influence their thinking.

Simply put, this research could have discovered truly bleak belief trajectories. (“If you tell me that cold calling is bad, I’ll stop believing research about vitamin D!”) Thomm’s research did not see that pattern at work.

Caveats, Caveats

Dan Willingham says: “one study is just one study, folks.” Thomm’s research gives us interesting data, but it does not answer this question completely, once and for all. (No one study does. Research can’t do that.)

Two points jump out at me.

First, Thomm’s team worked with teachers in Germany. I don’t know if German society values research differently than other societies do. (Certainly US society has a conspicuously vexed relationship with research-based advice.) So, this research might not hold true in other countries or social belief systems.

Second, her participants initially “reported a positive view on the potency of research and indicated a higher appreciation of scientific than of non-scientific sources.” That is, she started with people who trusted in science and research. Among people who start more skeptical — perhaps in a society that’s more skeptical — these optimistic patterns might not repeat.

And a final note.

You might reasonably want to know: what’s the answer to the question? Does repeating a year help students?

The most honest answer is: I’m not an expert on that topic, and don’t really know.

The most comprehensive analysis I’ve seen, over at the Education Endowment Foundation, says: NO:

“Evidence suggests that, in the majority of cases, repeating a year is harmful to a student’s chances of academic success.” (And, they note, it costs A LOT.)

If you’ve got substantial contradictory evidence that can inform this question, I hope you’ll send it my way.